Corporations: Publish Your Abuse Email Address!

In 2025, there is no excuse for a large organisation to not have an easily findable abuse reporting email address on their website.

As the volume of malicious phishing spam continues to increase year over year (just a few of the first results from a quick Google search for “phishing spam increase: [1] [2] [3] [4]), the fraud and malware delivery attempts users are subjected to are increasingly sophisticated and plausible. Unfortunately, while “the average Joe” tends to understand that fraud and abuse are a serious concern, the specifics of detecting often slick, well-crafted emails (and calls) can challenge even jaded, well-informed users.

Even when a mail on its own might immediately put you on your guard, occasionally some contextual factor will make it more credible. Anecdotally, in the past months, I’ve received two mails and a call which not only looked exceptionally believable, but were made more so by the fact that (probably by pure coincidence – I hope) I had recently made purchases or transactions with the companies being impersonated.

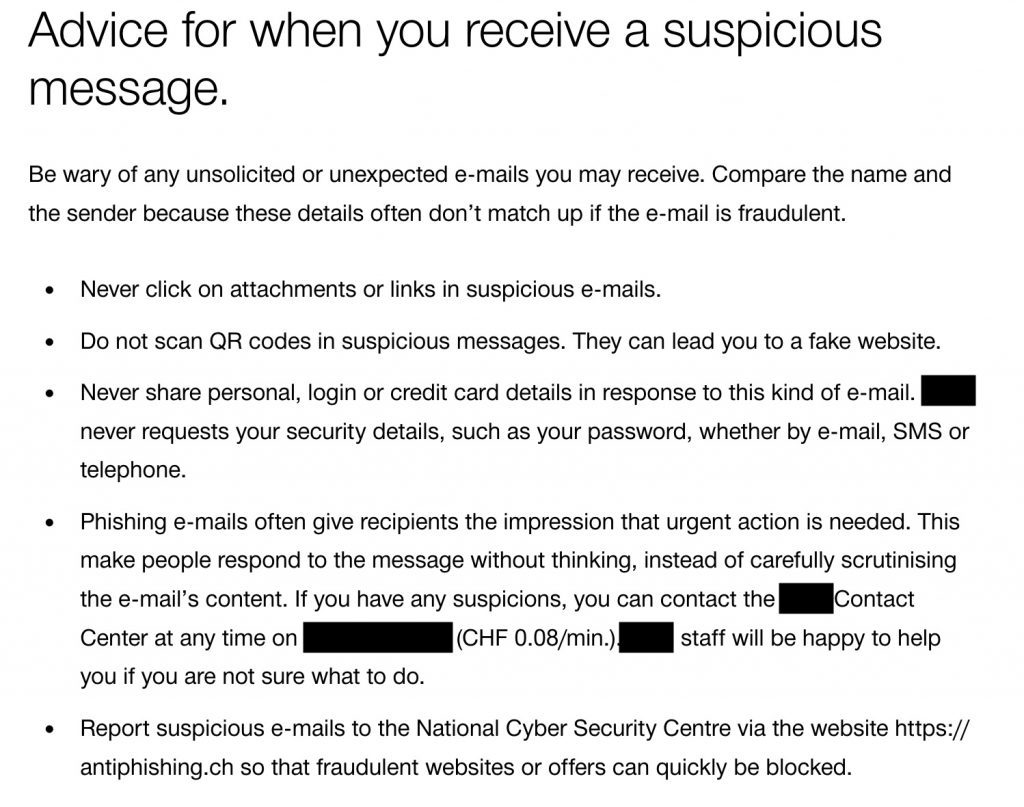

The last case motivated me to write this – reporting fraud and abuse should be easy and frictionless. It was…sort-of-but-could-be-better. The company in question has a decent, informative fraud page that includes a lot of information about what you will never receive from them and should/should not do, including the following:

- there is no easy way to forward fraudulent messages by email. I sent this one to abuse@ and haven’t received a bounce, so…

- The contact centre number is not freephone. Granted, this is Switzerland where nothing is free, but even small fees are a barrier to many people’s willingness to report or even ask questions

- There is no transparency about how the NCSC antiphishing resource interacts with the firm affected. Any organisation beyond a certain size that deals with significant numbers of B2C financial transactions should make every effort to receive any information that could improve both the information and resources it provides to its customers about detecting and avoiding scams, and its own technological capabilities such as how emails are formatted, how transactions are verified (e.g. via a corresponding app), etc.

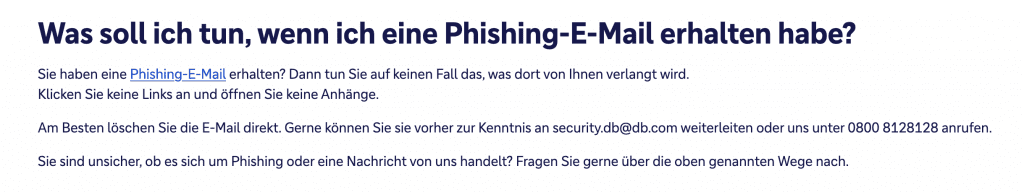

The above is not great, but it’s far from terrible – the main issue is the absence of an easily findable, obvious reporting address that is directed to an internal anti-fraud entity. Deutsche Bank is a great example of how to do this right:

There is a link explaining what a phishing mail is, short, simple, easily understandable instructions, and an email address + freephone number where you can get clarification or forward suspected fraudulent mails. Not only that, but relevant pages pop up at the top of search results for “Deutsche Bank betrug” (“fraud”) or “Deutsche Bank phishing”, no quotes on either search. This is good.

Yes, email scrapers will flood the obvious addresses with spam. Spammers will do this anyway. Abuse reporting addresses (e.g. abuse@, security@, fraud@, etc.) often exist and have obvious formats, and spammers have been extrapolating these from domain names and hitting them for >25 years. It is 2025, and if you’re not running an email filtering service that is sufficiently able to distinguish a legitimate report from garbage, you have no business being online.

A very cursory, completely non-scientific set of visits to the first few random corporate websites that came to mind includes four “categories” of reporting:

- No reporting tools / possibly some information about fraud and prevention

- Poor reporting tools with hurdles that will probably deter busy / non-technical users

- Reporting to some sort of central, shared anti-fraud resource (the above is an example of this)

- A published, easily accessible anti-fraud reporting email address or process

Proactively informing users about fraud is good, or at least, it can’t hurt. A good example that I recently received from one of my credit card providers in Spain:

There are no clickable links, and because the recipient isn’t searching for information about fraud, no information about contact phone numbers or email addresses. It is short, unambiguous, clear, and easily understandable. Unfortunately, when searching for similar resources as in the Deutsche Bank example earlier,

- the corresponding fraud website is a wall of text,

- it’s far down the list of search results, and

- there are zero contact options for forwarding mails or where to call with questions.

That is bad.

In short, you should be making every effort to collect information about scams impersonating your organisation from your customers as possible, not only offlloading the burden of blocking fraudulent sites to a CERT/NCSC or vendor.

A friendly shout-out to our friends at the Global Anti-Scam Alliance (GASA), who have a significant number of resources to help fight scams and fraud online.